"The human race is going to die in 4/4 time": The Out-of-Step Pagan Philosophy of Moondog

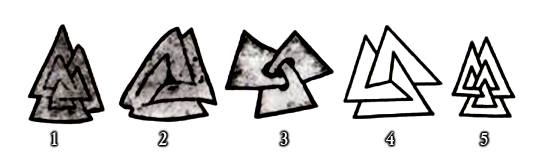

/Louis Thomas Hardin (1916-1999), aka. Moondog, is one of my greatest personal heroes. Among the most iconic figures of the American music underground, Moondog was seen almost every day at the corner between 53rd and 54th street and the Avenue of the Americas in New York City from the late 1940's to 1972. An dynamite-related accident left him blind as a bat at the age of 16, lending a distinctly Odinic look to this six foot tall character, who spent his days composing, and selling pamphlets of sheet music and poetry. Beyond that, he perhaps as famous for his music as he is for dressing in a viking inspired getup, consisting of hide shoes, poncho, cloak, and distinctly Wagnerian headdress, which was all too often mistaken for a childish publicity stunt. Making enemies in New York is easy, as Moondog biographer Robert Scotto noted, in a city that “offers a bewildering mix of talents and posers.”

Though the older Moondog looked like he had stepped right off the stage from Wagner's Ring Cycle, the young Louis Hardin was the son of a preacher, on a mostly bum-steered mission to convert American natives. Louis was greatly impressed by the otherness of their way of life, which would later prompt him to seek out a more primeval grounding for himself. His encounters with unflinchingly heretical chiefs offered him an alternative, authoritative point of view quite different from that of his father, who was lukewarm and distanced in all matters. His evangelical upbringing in an uncaring home resulted in his rejection of Christianity, and the staunchness of the Indians proved an excellent mirror to Moondog's own notorious stubbornness.

But it was the blinding accident that set the ball rolling: His creative thirst awoke when his sister read him Jesse Fothergill's novel The First Violin, a bildungsroman about an adolescent English woman studying music in Germany. This itself foreshadowed Moondog's own Teutonic journeys many years later. As he grew, his first encounter with the ancient North came by means of a braille transcription of Beowulf which, along with radio performances of Wagner, inspired the hope in him that he would one day write an opera of his own. His life as a composer proceeded with his move to New York in 1943, where he (barely) got by on street-level panhandling, and by posing for art students. He assumed the name Moondog in 1947, at 31 years old, in honor of a pet bulldog he once had that used to bark against the moon. He was yet unaware that the name in Old Norse, Mánagarm, is a poetic synonym for the mythological wolf Hati, destined to swallow the moon at the end of the world. The synchronicity later dawned on him, and Moondog shared with his mythological counterpart a certain contempt for the world he was dealt.

By 1948, Moondog had grown sick of New York and decided to leave “Coca-Cola culture” behind. He hoped to go live among the Navajo in New Mexico, but they firmly rejected him. He noted how they envied the culture he had left behind, while he coveted the culture they themselves were leaving. The final straw came when a group of them lead him between lanes on a busy highway and left him there. He traveled around the country instead, and by fall 1949 he was back in New York with a new elkskin cloak and square, wooden drum. Both of his own design. His awkwardly cut, “square clothes” and self-invented instruments would soon become emblematic of his unique musical style and personality.

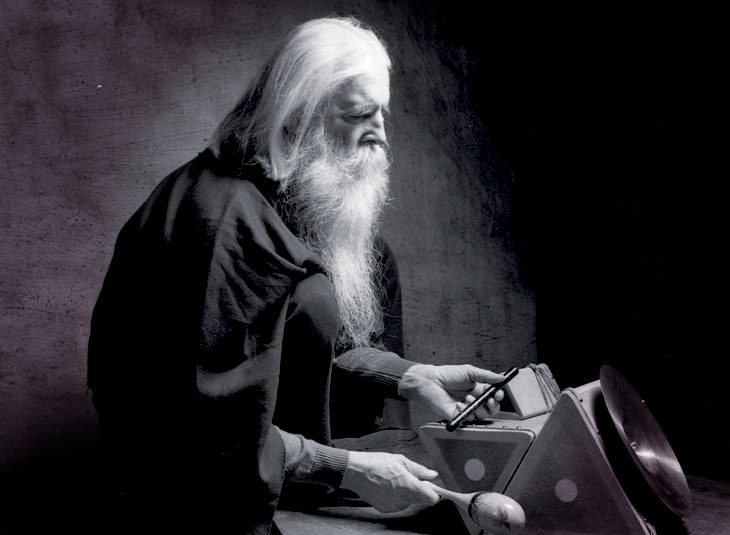

Moondog in his spot on 53rd and 6th.

Ever since Moondog first set foot in New York, he had the attention of celebrities, artists, hipsters, tourists, and flâneurs. Years before the full bloom of his “viking self”, he had already influenced, befriended, or been approached by today famous figures like Leonard Bernstein, Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, Dean Martin, and Bob Dylan. Muhammad Ali always referred to him as either “Moon” or “The Dog”. He performed with Tiny Tim and once jammed with Marlon Brando, who played the bongos. All the while, he was making five dollars a day on the street while sleeping on the floor of his record producer's basement. It was there he wrote “All is Loneliness”, a harrowing composition which would later be covered by a range of artists, including Janis Joplin, usually in far simpler rhythms than Moondog himself intended. The English folk-revival band Pentangle later recorded a song about him, and the Beatles may have plagiarized his name when they first started performing as Johnny and the Moondogs. David Bowie would later claim the sight of Moondog as his first distinct New York memory. He was less than enthusiastic about modern pop music: “The human race is going to die in 4/4 time”, he joked sardonically.

If people saw him as a living anachronism between the skyscrapers of Midtown, it should be said the feeling was mutual. Moondog claimed he never felt like an American. He idealized Northern Europe and referred to himself as a European in exile. When the music brought him to Germany in 1974, he was delighted to visit sites such as Teutoburg Forest, where Germanic tribes under the military leadership of Arminius lay waste to three Roman legions in the year 9 CE. As well as the Sachsenhain monument in Verden, where Charlemagne allegedly subjected thousands of pagan Saxons to forced baptism, before executing them en masse on the banks of the rivers Aller and Weser. These pilgrimages must have spoken to Moondog's yearning towards a more native and ancient atmosphere, as well as the Machiavellian sentiments of his personal philosophy. Every now and then, I make little pilgrimages of my own to Moondog's corner, where only his ghost remains to those who still remember, or are otherwise initiated into the secret of his existence.

While people tend to imagine Moondog busking on “his corner” on 6th Ave, this was not usual. For the most part, Moondog’s daily routine consisted of standing in the shadow of the Manhattan skyline, tapping along as he wrote music in braille. He composed poetry, sold his own sheet music, sipped coffee, relished the sounds and rhythms of the city, chatted with strangers, joked with friends, and disarmed hecklers, rain or shine. For his poetic and philosophical content he relied heavily on the mnemnonic wonders of poetry, much like skaldic poets and bards did in the absence of the written word. When he wrote these poems down, he usually kept it down to only a few keywords in braille in which the poems were immanent, and used them recall their poetic content and structure like a true singer of tales. He composed hundreds of simple couplets in iambic septameter, mapping his unique view of the world. Here are but a few:

᛫ It seems that hills are made to fall, that dales were made to rise,

that mediocre nondescripts were made to compromise.

᛫ The only one that knows this ounce of words is just a token,

is he who has a ton to tell, but must remain unspoken

᛫ We grope with eyes wide open toward the darkness of futurity,

with faith in outermost instead of innermost security.

᛫ We were few and far between in prehistoric times,

and we'll be few and far between in posthistoric times.

᛫ There was a time when goods were made for wear instead of tear.

There is a time when goods are made for tear instead of wear.

Moondog in Hamburg in 1974. Copyright: Beatrice Fehn, via Moondogscorner.de

Extraordinary expectations often follow extraordinary appearances. The bizarre viking image that made him so famous was, and is, far too often mistaken for a device he used to bring attention to himself. Moondog's image may have been carefully crafted, but was not intended as a cheap publicity stunt. Rather, it was an expression of who Moondog truly thought he was. Though his weirdness gained him some notoriety, it was also an opportunity for his critics to lash out against him. Some considered him no more than a naive autodidact, whose eccentricities awarded him undeserved fame. Even in the avant-garde, Moondog remained an outsider throughout much of his life.

For one thing, Moondog considered himself a sort of pagan. “I believe in the Norse gods,” he said. “When you think of the deity, you raise up your head, you just salute the invisible; it can happen any time; if you feel like communicating with something beyond humanity, you just do it.” Moondog's out-of-step spiritual convictions often go overlooked or understated when people write about him. No wonder: The average member of the public will have enough trouble coping with the weird viking costume, never mind making sense of the exotic and strange spiritual realm he inhabited. But to be fair, his odd brand of pagan ideas are idiosyncratic even by Modern pagan standards. Moondog longed for a different time and place, more 'true’ and authentic to his being. The clothes symbolized his rejection of those chronological and spiritual circumstances he was born into, as well as his strong affinity for the Nordic pre-Christian traditions. His fascination with the subject matter may have been difficult to reconcile with the sexy mystique of jazz, the music press, and the gatekeepers of the classical music intelligentsia. But it pervades his work, and he kept bringing it up in interviews. To add further emphasis with his syncopated out-of-stepness with modernity, he operated with an alternate calendar system of his own design, with the dawn of agriculture as its point of departure. Moondog's year zero is 8000 BCE to us.

A poem submitted by Moondog to the Norwegian-American newspaper Nordisk Tidende, December 30th, 1965.

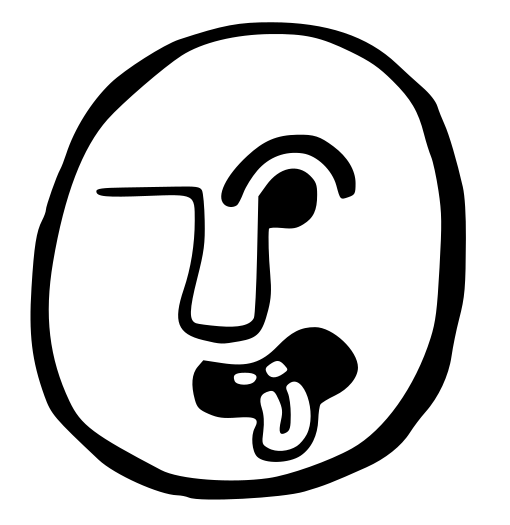

Even if the spiritual dimension of his aesthetic and musical life never gained traction with the media or public, his notions about a pagan revival outside of the confines of centralized religion seem to have gone with him wherever he went. Throughout his work he made many surprising references to Norse culture. For example, the dense and esoteric title Logrundr, which he used for a large cycle of numbered compositions, is comprised of the Old Norse words lǫg meaning law or canon, and grundr meaning ground. In a different, musicological sense — Moondog's sense — ground is a repeating bass pattern played under a cascade of musical variations. This is technique is essential to Moondog's cataolog. Then there's the Heimdall Fanfare, a monumental rally composed for nine horns. Ginnungagap, Hugin and Munin, Buri - Bor, the heroic-lyrical Thor and the Midgard Serpent, and the epic poem Thor the Nordoom, to name a few. Some monumental compositions, like his magnum opus The Creation — based on the Norse cosmogony —, have only been partially performed. Most of his overtly pagan material was never formally published or recorded, at least not by himself. He envisioned a grand Edda Day ceremonial on the summer solstice. This was supposed to be a festival of avant-Nordic (dare I say, Scandifuturist?) panegyric celebration. A feast of poetic recital, musical performances, and ecstatic dance. In one sense, this dream was realized in a performance at the royal mounds in Uppsala in 1981.

Moondog at the Royal Mounds in Uppsala, 1981. Copyright: Stefan Lakatos, via Moondogscorner.de

One, seemingly more incidental recording reveals much more about Moondog's inner nature than you first may think: Frey and Freya Chewing on Two Big Soup Bones is exactly what the title states. However, it's not the gods Frey and Freya the title refers to; it's his dogs. In one recording he says:

“That's a great sound, you know, it’s... You can, you can see what's going on, you can see it all just from the sound, you know. All those white teeth shining there in the night, in the moonlight, yeah. There's snow all around. You can hear them breathing there as they're chewing. That's a very primitive sound. Oh my, it's primitive.”

For what Moondog lacked in eyesight, his vision burned bright in the world of noises. He loved all kinds of sounds, whether the symphonies of Bach or the rattle of the passing A train going up and down Manhattan. Though he insisted on a mutual rejection between himself and the modern world, the rattling of the subway train never seems far away in Moondog's “snaketime” rhythms.

Where but New York could such a man come to exist? Nevertheless, he ended up relocating to Germany in 1974. By then he had become so ingrained in the New York scene that many simply assumed he had died. Rather, it was in Germany that he enjoyed many of the fruits of his labor, living as a composer and touring musician until he died at the age of 89 in 1999. Or rather the year 9999 according to his own calendar.