Olde English Malt Liquor (Review): 24 Ounces of Anglo-Saxon glory

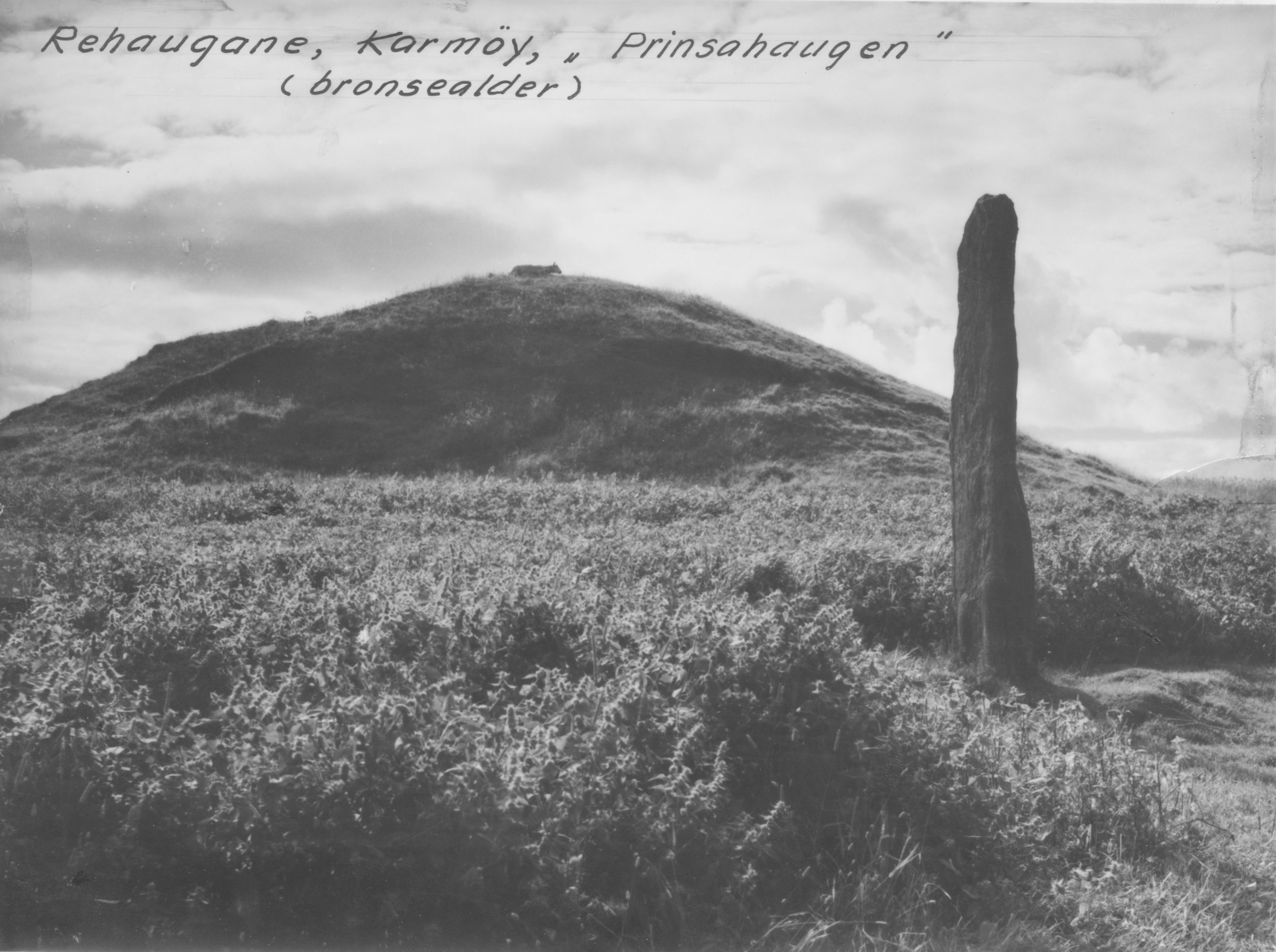

/America doesn't have much viking related stuff to see besides runestone-based hoaxes and the odd statue of Leif Erikson. That's cool enough on their own terms, though I haven't had the chance to see any during my trips. Not that it matters. There's enough to see and do in my base camp in New York, which is chock full of beautiful museums and great art. Luckily, I'm bestowed with other fascinations as well. For example, I'm extremely interested in the sociology of drinking culture. Or really just drinking culture in general. Or maybe I just like drinking? Who knows.

I'll read a demographic report on national alcohol consumption with childlike curiosity, so I've spent hours hauling my girlfriend from liquor store to liquor store. I hardly ever bought anything, though: For the most part I was really just comparing booze selections in various parts of the city, which lead me to conclude that Americans of all social classes really love their IPAs.

It was in some sticky-floored bodega I saw it. A bronze can winking at me from the refrigerator at midnight. The label stated Olde English "800" malt liquor. The holy grail and envy of post-ironic Medievalists across the Western hemisphere. This is what Beowulf would have drunk were he a hobo in Detroit. What does the "800" stand for? I have no idea, but 800 was a year in the early viking era, which must mean I'll take any excuse to write an article. Being somewhat of a historian of human and animal alcohol abuse, as well as an expert in certain cultures long since dead, I was pretty stoked to try it out. I took out of the fridge and carried it to the counter with both hands and gave a cheery nod to the proprietor – an unenthusiastic Asian man. I paid in cash and carried it home in a brown paper bag.

What is malt liquor? Let me tell you: Malt liquor is basically potent beer, often sold dirt cheap in large containers. Why don't they just call it beer, then, you might ask. They don't, because that would be illegal in several states, that's why. Instead malt liquor is an umbrella term used for various alcoholic beverages made with malted barley, but usually contains various industrial grade non-standard ingredients to cheaply boost the alcohol level as well. Malt liquor, malt liquor, how it rolls off the tongue.

For context: The Norwegian welfare state is very concerned with the health of its citizens, which means it's prone to nanny-state lawmaking. We have a restrictive alcohol policy, and hard alcohol is only available through a government-run chain of liquor stores. It's not all bad: Two benefits to this is a monstrously huge selection and a thoroughly educated staff. It also means that everything they sell is curated by a board of specialists. This so-called Wine Monopoly does provide both higher and lower quality booze. But they don't offer gut-rot products such as what Americans call bum wine, which tastes like a chemical spill and allegedly makes your tongue turn black, so it's probably for the better. American malt liquor is rarely exported as well, and demand will never be large enough for the Norwegian Wine Monopoly to care. This combined with a general counter-cultural interest, may explain why these beverages hold an almost mythical status to me. Make no mistake, however: Produced by MillerCoors, one of Americas highest grossing brewing companies, Olde English "800" is no underdog by any means. The international beverage industry is cynical and deceptive.

Back in the apartment I sat down, wondering whether I should have a meal or a snack, but in the end I could come up with no better pairing for Olde English "800" than Anglo-Saxon Books' parallel translation of Beowulf. Luckily, a copy happened to be within arms reach. I politely tapped the can to warn the contents of my arrival, put my finger to the tab, cracked it open and had a sip. I halfway expected it to be really awful. It's certainly no taste explosion, but I can't honestly say it was in any way lesser in quality to cheap macro lagers such as Budweiser (so-called " " "king" " " of beers) or Pabst Blue Ribbon (hipster soma). In fact, I found the morning-urine-hued, Anglo-Saxon themed drink to be richer in taste than both of them despite a rather low hop profile. Then again, this is probably carried by the comparatively hearty alcohol content of at 5.9% AB. It is what it is.

Verdict:

Three cleft skulls.

Best paired with poetry in a dead Germanic tongue and bitter musings on the Norman invasion.

[First published March 22nd 2017]